|

|

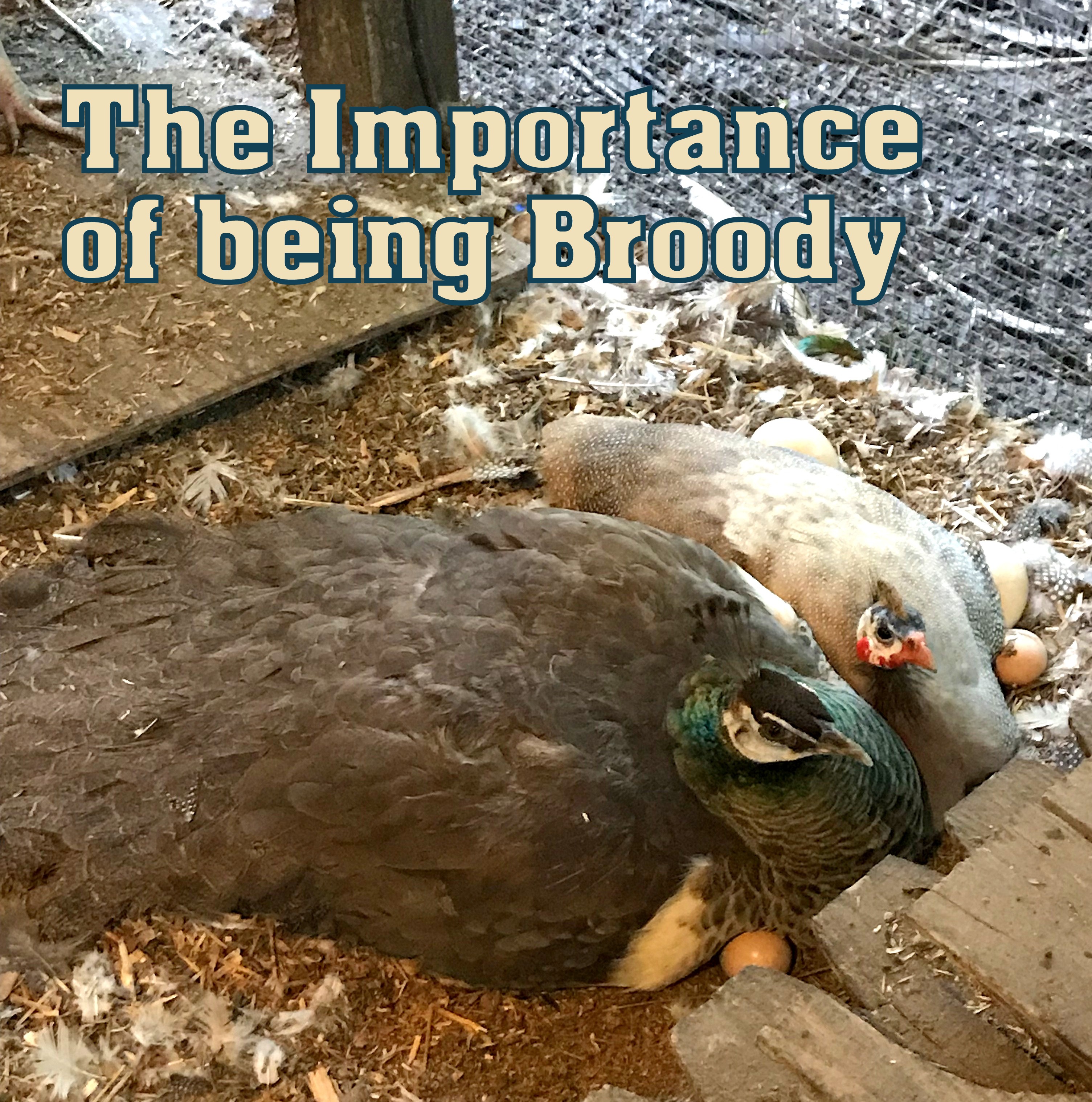

In the world of backyard chicken keeping, I read inconsistencies about bird behavior and what is "good" and what is "bad", especially when it comes to the broody condition of hens. I think it is because people seem to label any bird process depending on what the chicken keeper wants for an end result. For example, if a hen goes broody and the chicks are wanted, it is a highly anticipated event then broodiness is good. However, if the hen is sitting on non-fertile eggs (no rooster) or more chicks are not wanted, the health of the hen suddenly becomes a grave concern and broodiness is bad. Or, the chicken keeper is inconvenienced to have a hen stop laying eggs while she is broody so broodiness is again, bad. Having a personal stake in broodiness and what it does, or does not do for us, is not the right approach. We have to understand how and why it happens and what it means to the hen and the social structure she lives in, which will influence her behavior. Domestication and selective breeding over the last century has made a big difference in poultryís natural behaviors that are vastly different than their ancestors. It has been shown that breeding out qualities like reduced broodiness and increased egg production may be genetically linked to increased aggressive behaviors. We have seen it in roosters who have lost their ability to court and dance with a hen during mating, and have become ďrapistĒ roosters. In todayís breeding genetics of commercial domestic chickens, broodiness is not needed. The commercial industry can hatch their own eggs in incubators. A broody hen means a loss of eggs which is what commercial operations need hens for. So these genetic qualities through time have been bred out, or at least not encouraged. Some researchers believe there is no harm done, but I find this sad, because I think there is a loss to their social health. We know of hens who leave the nest before the eggs are hatched, their broodiness is hit and miss, or who donít bond well with chicks. Dealing with behavioral issues are partly due to genetics, but also it has to do with our own management. The good news is that brooding behaviors are controlled by both internal and external factors. The henís nervous system has the capacity to change structure and function to adapt to their environment. This is an important point if you want to encourage your hen to do the best she can with the genetics she has. But that means to let her fully participate in the social structure. First we need to understand the biological process which causes a hen to go broody. Broodiness and egg laying in a hen is largely dictated by a hormonal cascade to facilitate egg laying and broodiness. Light can stimulate the pituitary gland, to generate an abundance of hormones. Incubation and broody behavior is controlled by the hormone prolactin. Prolactin stimulates nesting behavior and promotes the development of the brood patch on the hen. If you allow a hen to brood, it will induce more prolactin receptors in the brain. The larger numbers of receptors will then enables stronger maternal responses. Conversely, if you inhibit the effects of prolactin, it will reduce likelihood of broodiness. That is why if you allow broodiness in a hen, she will increasingly become a very attentive mama and can be counted on to go broody as she gets older. Most poultry are social animals, but you may not know they are also inherently competitive as part of their social structure. The social structure is very important and it will dictate the heath of their behavior Poultry compete for just about everything in their environment, including mating, feed, preferred locations, parental care, nesting areas and pecking order etc. Good management with large enough housing, runs and free ranging is extremely important. Feeding and water stations should be plentiful enough as needed to reduce harmful competitiveness. Gender ratios and size of flock and even the breeds you have also matters a lot. For example, the ratio of males to females will affect behaviors. Too few, or no roosters at all, can lead to hormonal changes in hens to take on male characteristics like crowing or aggression. Mixing a lot of different breeds should be thought about long and hard. They can have different living and social requirements. Natural breeding behaviors are also part of the social structure. As hens actively becomes reproductive through the hormone cycle, including egg laying and brooding, they will become accessible to males to mate by squatting down. The roosters on the other hand through their own hormones become more aggressive and competitive. Females who have been broken of their broodiness, who are not yet back in the hormonal cycle of egg reproduction, can be faced with an overly aggressive male who wants to mate and the hen will not be receptive to that. If you break a hen of broodiness, you are not just breaking the hormonal cycle, but also breaking the social structure of living. I let my hens stay broody on the nest, without eggs, if I donít want chicks until the broody cycle completes. I set food and water nearby to keep her nourished, often times with an herbal supplement. I offer this whether she is sitting on eggs or not. When she is done her body will resume their natural hormonal cycling. Rather than breaking a hen of broodiness, I can offer some tips to help minimize it. Collecting the eggs everyday will help. There are trigger points after laying a certain number of eggs for a clutch that can help increase prolactin to induce brooding. A hen responding to environment changes (no eggs) can perhaps keep this hormone level from rising. Keeping your coop full of light can also discourage broodiness. Dimly lit nesting boxes, especially with curtains, will only encourage it. Hens are not looking for privacy so much as a place to brood eggs. Encouraging your flock to live out their natural competiveness and hormonal cycles will help them manage their social structure behaviors they are hard-wired for.We as backyard chicken keepers have an opportunity to raise our flocks to be able to freely express their natural behaviors. Source: Susan Burek 2019 Source: Poultry: Behavior and Welfare Assessment J.A. Linares, M. Martin, in Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, 2010 |

Moonlight Mile Herb Farm © 2020 Susan Burek